Even Dr. Frankenstein and his monster would be jealous of this creature.

Paleontologists have unearthed the fossil of an ancient crab that lived between 90 and 95 million years ago and is so "utterly bizarre" it literally perplexed the researchers.

Known as Callichimaera perplexa, which means "perplexing beautiful chimera," the crab had an assortment of body parts that would make Mr. Potato Head green with envy.

'GIANT LION' FOSSILS DISCOVERED IN MUSEUM DRAWER

“We started looking at these fossils and we found they had what looked like the eyes of a larva, the mouth of a shrimp, claws of a frog crab, and the carapace of a lobster,“ said Javier Luque, lead author and postdoctoral paleontologist in the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Alberta and at Yale University, in a statement.

Luque continued: “We have an idea of what a typical crab looks like—and these new fossils break all those rules."

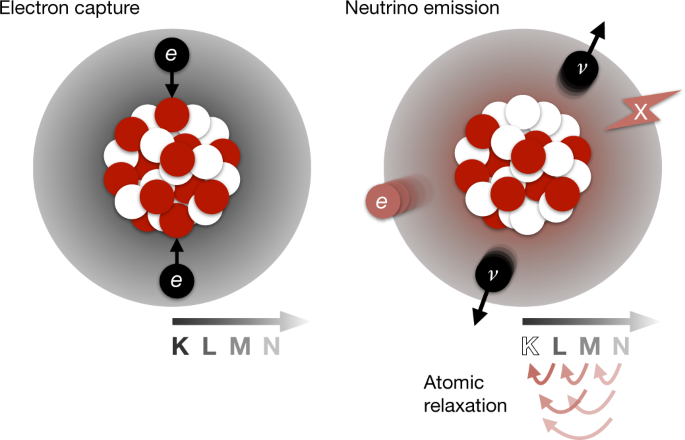

An artistic reconstruction of Callichimaera perplexa: the "strangest crab that has ever lived." (Credit: Oksana Vernygora, UAlberta)

In Greek mythology, a chimera had the head of a lion, the body of a goat and the tail of a snake.

The researchers wrote that the discovery and C. perplexa's body type challenges the conventional view of what earlier crabs looked like. "Our phylogenetic analyses, including representatives of all major lineages of fossil and extant crabs, challenge conventional views of their evolution by revealing multiple convergent losses of a typical 'crab-like' body plan since the Early Cretaceous," the study's abstract reads.

The study was published in the journal Science Advances.

The crab's giant eyes likely helped it to hunt smaller crustaceans while swimming in the ancient Cretaceous period oceans. "We don't think they were filter feeders," Luque told Live Science. "We think they were actually active predators."

C. perplexa was first discovered in 2005 in the Andes Mountains, along with other ancient crustaceans such as lobsters and shrimp. Since then, Luque and a team of researchers have analyzed the fossil (no bigger than a quarter) in great detail and suggested that it spent its life swimming, in stark contrast to modern-day crabs, who spend their lives crawling.

FOSSILIZED REMAINS OF 430 MILLION-YEAR-OLD SEA MONSTER FOUND

“We found dozens of animals, from tiny baby specimens to mature individuals in which we found reproductive organs—a smoking gun that proves these were adult organisms and not larvae. We can even see individual facets on the large compound eyes of these creatures,” Luque added in the statement. “It’s an incredible amount of detail, and we’ve been able to reconstruct them like they were living yesterday."

Callichimaera perplexa: the oldest swimming crab from the dinosaur era. (Credit: Daniel Ocampo R., Vencejo Films)

Luque said that it's not unusual to find different body types in older rocks, as life was still expanding into new forms.

“This discovery, from the mid-Cretaceous, illustrates that there are still surprising discoveries of more recent, weird organisms waiting to be found, especially in the tropics," he concluded. "It makes you wonder ‘what else is out there for us to discover?’“

CLICK HERE FOR THE FOX NEWS APP

https://www.foxnews.com/science/bizarre-chimera-crab-fossil-discovered

2019-04-25 14:16:49Z

52780276414893